Ecological drivers of range limitation in species

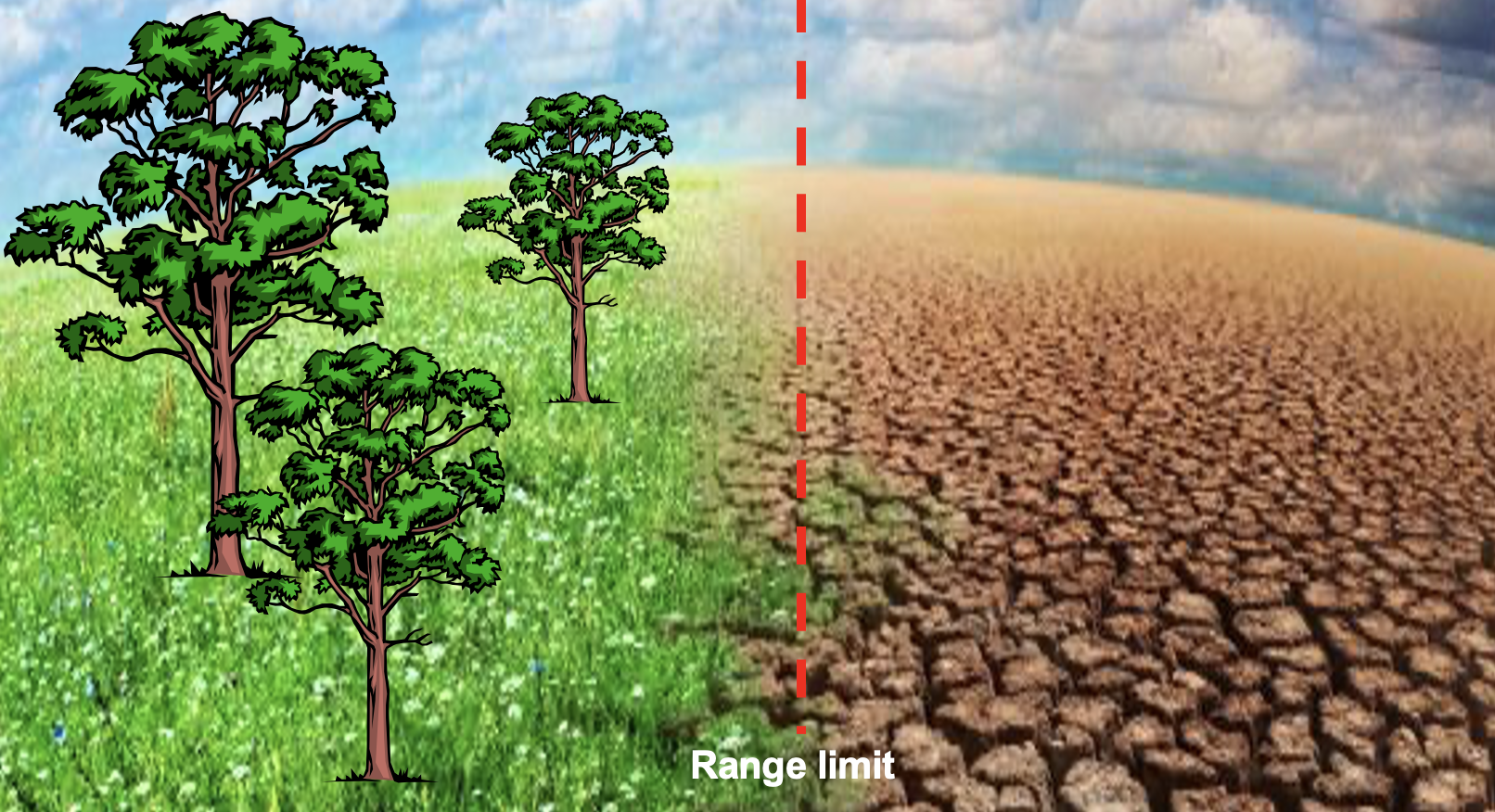

Understanding the ecological and evolutionary drivers of species range limitation is a central debate in evolutionary ecology with direct implications for conservation ecology. This is important because such understanding provides insights into the mechanistic drivers of species adaptation or extinction in peripheral populations where species are often exposed to severe and stochastic biotic and abiotic stressors. The center-periphery hypothesis posits that species performance decreases toward range periphery, a potential mechanism to explain range limitation. However, after several decades of testing the center-periphery hypothesis, we still lack general support for this hypothesis. In this project, I combined meta-analysis, field observation, and modeling to gain general understanding of the drivers of range limitation using the center-periphery hypothesis.

Understanding the processes that generate limits on species’ geographic distributions is a classic problem in ecology that takes on urgency in the face of rapid environmental change. There is wide recognition that species interactions, together with abiotic forcing, may play a key role in shaping geographic distributions. However, current theory and data overwhelmingly focus on antagonistic interactions like consumption and competition. This project will test the influence of mutualism between host organisms and their microbial symbionts on the geographic distributions of both partners under current and future climate scenarios. Using a generalizable model system with a well-developed toolkit (cool-season grasses and their vertically-transmitted fungal endophytes), this project will combine geographically distributed symbiont removal experiments, demographic range modeling, climate change forecasting, collections-based surveys, and genetic profiling of symbionts to measure, for the first time, the geographic footprint of host-symbiont mutualism.

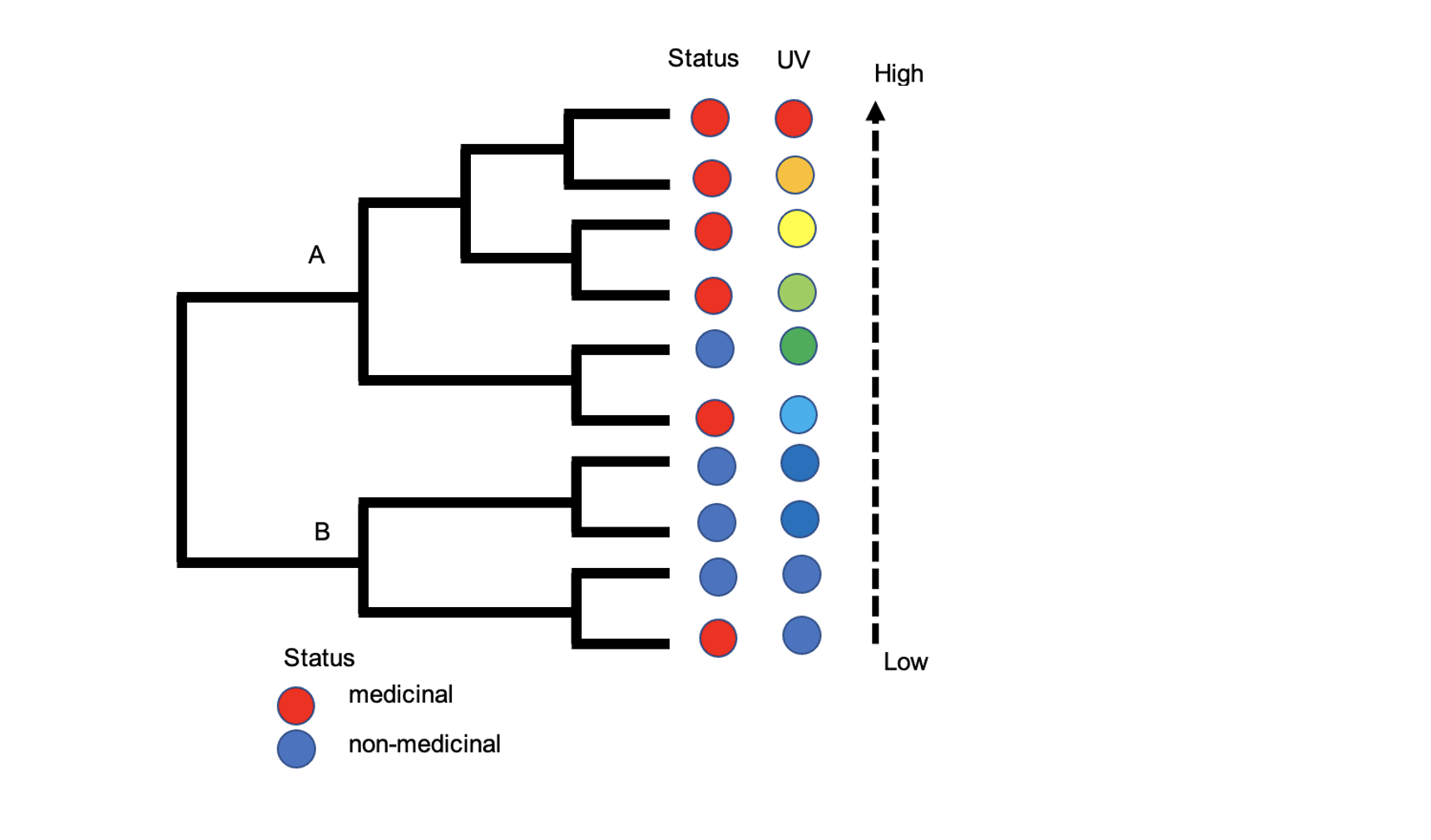

Hypothesis‐driven ethnobiology

Ethnobiology as a discipline has evolved increasingly to embrace theory-inspired and hypothesis-driven approaches to study why and how local people choose plants and animals they interact with and use for their livelihood. However, testing complex hypotheses or a network of ethnobiological hypotheses is challenging, particularly for datasets with non-independent observations due to species phylogenetic relatedness or socio-relational links between participants. However, testing complex hypotheses or a network of ethnobiological hypotheses is challenging, particularly for datasets with non-independent observations due to species phylogenetic relatedness or socio-relational links between participants. This project seeks to use advanced statistical methods to test major ethnobiology hypotheses. This type of study could be used as a guide to design conservation actions for over-exploited species in tropical regions where local people rely heavily on medicinal plants for their healthcare.